A Beekeeper's Journal: Anticipation and Preparation

March 22, 2023

by Martine Gubernat

Winters and the Mite Problem

As somewhat experienced beekeepers, we are aware of the challenges of getting our colonies through the mercurial spring, the hot and dry summer, the wet fall, and the unpredictable winter to emerge alive and well the following year in the very early spring. To that aim, we pampered and coddled our bees like overly protective mothers, determined to make our bees’ lives as happy and safe as possible.On one of the warmer days last year in January 2022, when the temperatures rose to around 50 degrees, we added the first mite treatment of the year to each of our six hives. We removed the outer cover, insulation board, and inner cover for just a few minutes in order to insert two strips between the frames in the top box where we saw the bees clustering. Tempted as we were to look deeper inside the boxes, we promptly closed up each hive once the miticide was installed in order to disturb the bees as little as possible.

Varroa mites migrated from Asia to the United States in the late 1980s and have created problems for honey bees and beekeepers ever since. Left untreated, they can decimate a colony in a few months. That particular miticide must stay in the hive for 56 days and is then removed at least 14 days before the honey supers (the boxes where the bees store honey) are added to the hives. This treatment was an important first step to safeguard our honey bees.

Bee Cleanliness

Beginning in March, we eagerly watched the bees flying in and out of the hives on days when the temperature topped 50 degrees. The tell-tale signs that the bees were out and about are the small, yellow dots on our car windshields — honey bee poop! Amazingly, the honey bees never defecate in their hives because they are hygienic and instinctively know that the inside of the hive must remain clean so as to avoid the spread of disease and contamination of honey, so they take “cleansing flights” when the weather permits.When the temps are too cold for them to leave the warmth of the hive, they hold it in! One exception for this behavior is the queen, who does not leave the hive after returning from her one and only mating flight. When the queen poops, her attendants clean the waste from her body. It is good to be the queen!

Early Spring Beehavior

In March, we also noticed that the honey bees were bringing pollen back to the hives as indicated by the colorful white, yellow, and orange bulges on their “pollen pockets.” When bees visit flowers, the pollen sticks to the tiny hairs on their bodies. Using their legs, they comb the hairs to collect that pollen, moisten it with their saliva, and pack it into an area on their back legs, which enables them to carry it back to the colony.When they return to their hive, those forager bees unload their pollen pockets and stuff it into the wax comb cells. Pollen serves as protein for the bees and is a key ingredient in the food that the nurse bees feed to the developing larvae. It is also an integral component in royal jelly — the essential food of a developing queen. The presence of many bees entering the hive with pollen pockets is an indication that the queen will start ramping up her egg laying. Once the weather is warm and the nectar is flowing, the queen will lay up to 2,500 eggs every day. The colony will increase in population to between 50,000 to 75,000 honey bees!

Temperatures Warming Up

Throughout the early spring and summer of 2022, especially during the extreme heat and lack of rain, our daily routine included refilling strategically placed bird baths around the yard so that the honey bees had a constant supply of water.Bees are sometimes drawn to swimming pools — both chlorinated and salt water — in search of minerals, but we did not want neighbors to be upset about sharing their swimming space with bees so we set up our water sources months earlier than the neighborhood pools were opened in order to “train” the bees. They are creatures of habit and once they locate a good source of water (or nectar, or pollen), they will return to that familiar location.

Honey bees use water to regulate the temperature of the hive, to feed young bees, and to dilute stored honey that has crystalized. After initially seeing some of the bees floundering in our bird baths, we added small stones and twigs so that the bees had landing spots where they could safely walk down to the water to get a drink without landing in the water and drowning.

Post-First Honey Harvest

After harvesting some honey in early July (light honey), mid-August (amber honey), and mid-September (dark amber honey), we fed the bees sugar syrup with Honey-B-Healthy, which we liken to giving vitamins to children. Because the hot, dry summer resulted in a nectar dearth, we did not extract as much honey as we have in previous years. Honey, a carbohydrate, is an energy source for the hard-working bees so we wanted to be sure to leave enough inside the hives for each colony to eat.We also treated the colonies twice more for mites in 2022 — in mid-July and in late-September because, as one of our beekeeping mentors told us, the mites are a factor we can control to a significant degree. We always make sure to rotate treatments so that the mites do not build up a resistance to the miticides; additionally, some treatments with naturally occurring substances (such as oxalic acid) can be used safely when honey supers are on the hives while other treatments cannot be in the hives when the honey bees are bringing in nectar. Unfortunately, treating for mites has become a necessary part of beekeeping and we equate ignoring that responsibility to not treating a dog that has fleas.

Temps Cooling Down Again!

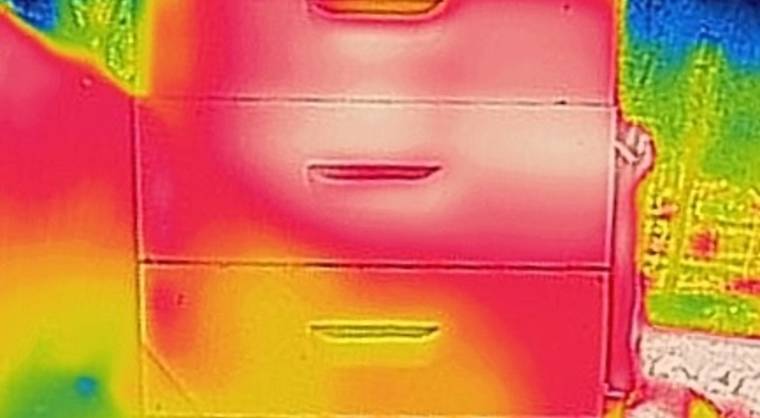

In November, when the winter winds began to blow, we hammered stakes into the ground and tacked up a wind block tarp a few feet in front of the hives to limit the frigid air from blowing past the entrance reducers.We added patties of homemade fondant above the inner covers so that the bees could access snacks throughout the cold season in case their honey supply diminished. We also snuggled them up by surrounding them with custom cut, two-inch thick rigid foam board insulation the way a mother would wrap her children in warm clothes before sending them out to play in the snow. While the bees do not necessarily require this extra layer of insulation, it does help keep the inside of the hives a bit warmer so that the bees do not have to expend as much energy vibrating their little bodies to produce heat as they cluster around the queen. Check out the infrared heat photo above! Can you see the cluster?

Conclusions

All winter we crossed our fingers and hoped that our year-long beekeeping efforts would pay off. Yes, we invested a considerable amount of money and time to purchase, assemble, and paint our equipment but more than that, we had invested our emotional energy into our honey bees’ wellbeing.So on an unusually warm day in February 2023, when the bees were flying in and out of all six of our hives, we could not have been more pleased. Our sense of accomplishment, and the honey, will be sweet indeed!

Speaking of sweet, while I am drinking hot tea on chilly winter days, I love to add Adagio Bees' Sourwood with its light hints of maple and spice. I recently discovered that someone in my neighborhood has a sourwood tree, so I hope that my bees discover it when it is in bloom!